Marcury

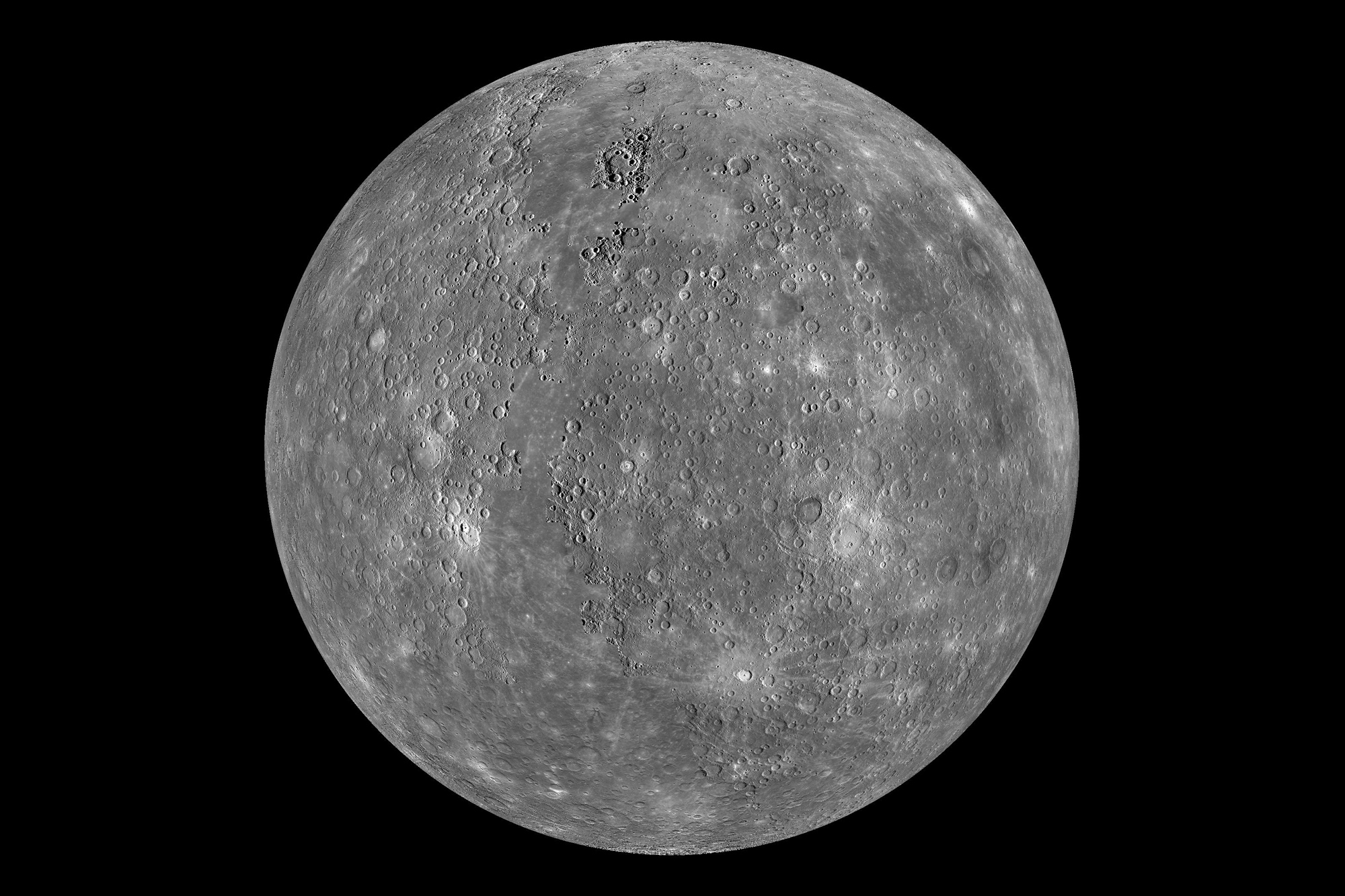

Mercury — the closest to the sun and the second smallest planet in our solar system, Mercury has a rotation of only 88 days around the sun. Because of its close proximity to the celestial giant, the surface of the planet reaches temperatures as high as 840°F during the day and hundreds of degrees below the freezing point at night. There is no atmosphere due to the intense temperatures so the planet's surface is covered with pock marks and craters from meteor impacts.

Mercury — the closest to the sun and the second smallest planet in our solar system, Mercury has a rotation of only 88 days around the sun. Because of its close proximity to the celestial giant, the surface of the planet reaches temperatures as high as 840°F during the day and hundreds of degrees below the freezing point at night. There is no atmosphere due to the intense temperatures so the planet's surface is covered with pock marks and craters from meteor impacts.

Venus

Venus this toxic planet, primarily consisting of carbon dioxide, is next in line from the sun and contains a pressure index that would crush anyone who landed on its surface. Though it is further away from the sun then Mercury, Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system and is able to be seen by the naked eye from Earth. A thick cloud shrouds the planet, making it difficult to see its surface which attributes to its brilliance.

Earth

Earth — is the planet in which we live on and is the 3rd planet from the sun. Also known as "Terra" the Earth is the only planet within our solar system that is capable of sustaining advanced life forms, such as humans. The Earth's rotation around the sun is approximately 365 days and it is believed that the Earth is approximately four thousand million years.

Earth — is the planet in which we live on and is the 3rd planet from the sun. Also known as "Terra" the Earth is the only planet within our solar system that is capable of sustaining advanced life forms, such as humans. The Earth's rotation around the sun is approximately 365 days and it is believed that the Earth is approximately four thousand million years.

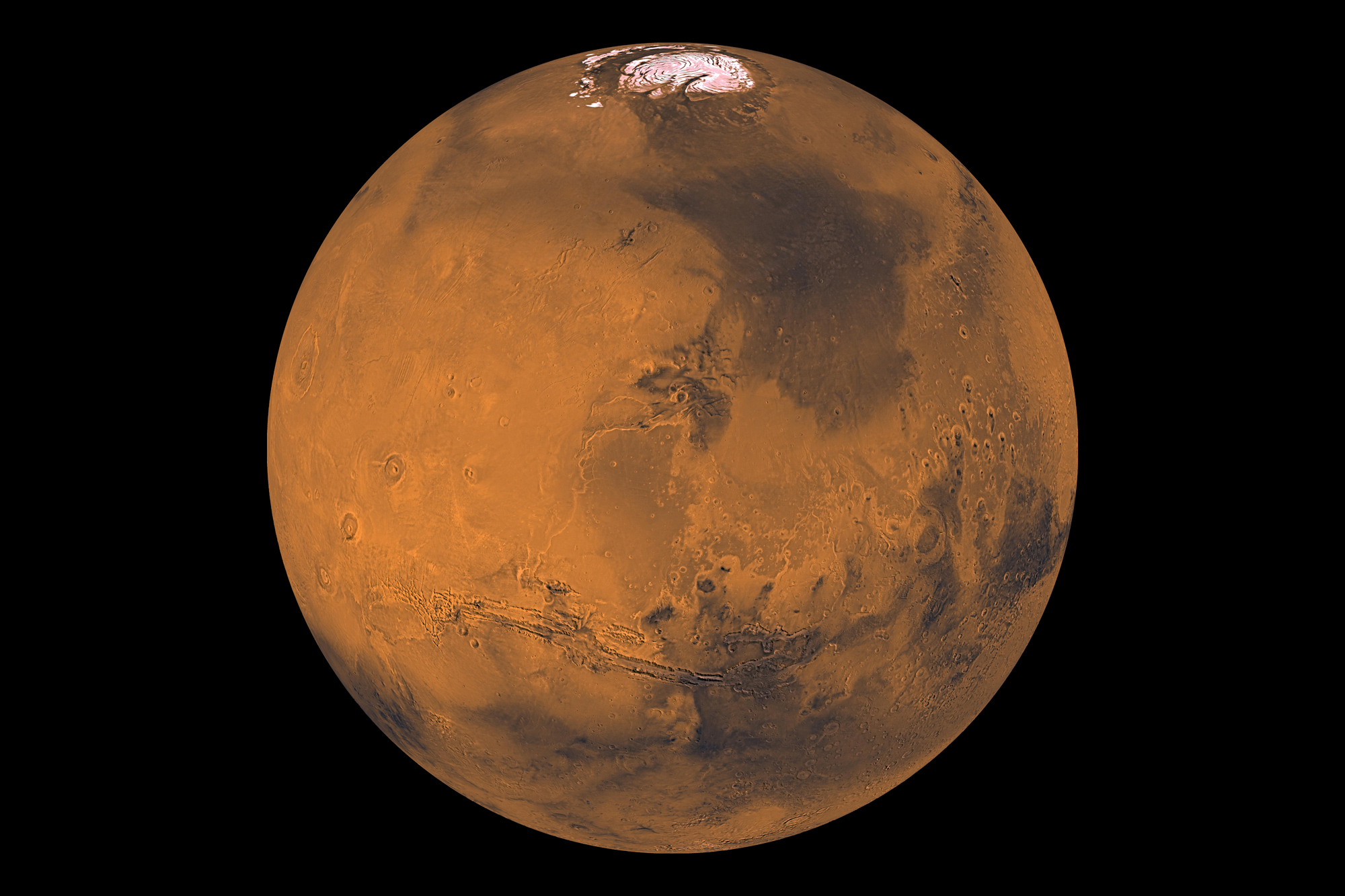

Mars

Mars — the fourth planet from the sun the "red planet", so named for its reddish color due to the high iron content in its soil, has a rotation around the sun of 686 days. Its thin atmosphere, consisting primarily of carbon dioxide, makes it unsuitable for sustaining life, but is believed to have at one time been capable of it and might still be able in the future.

Jupiter

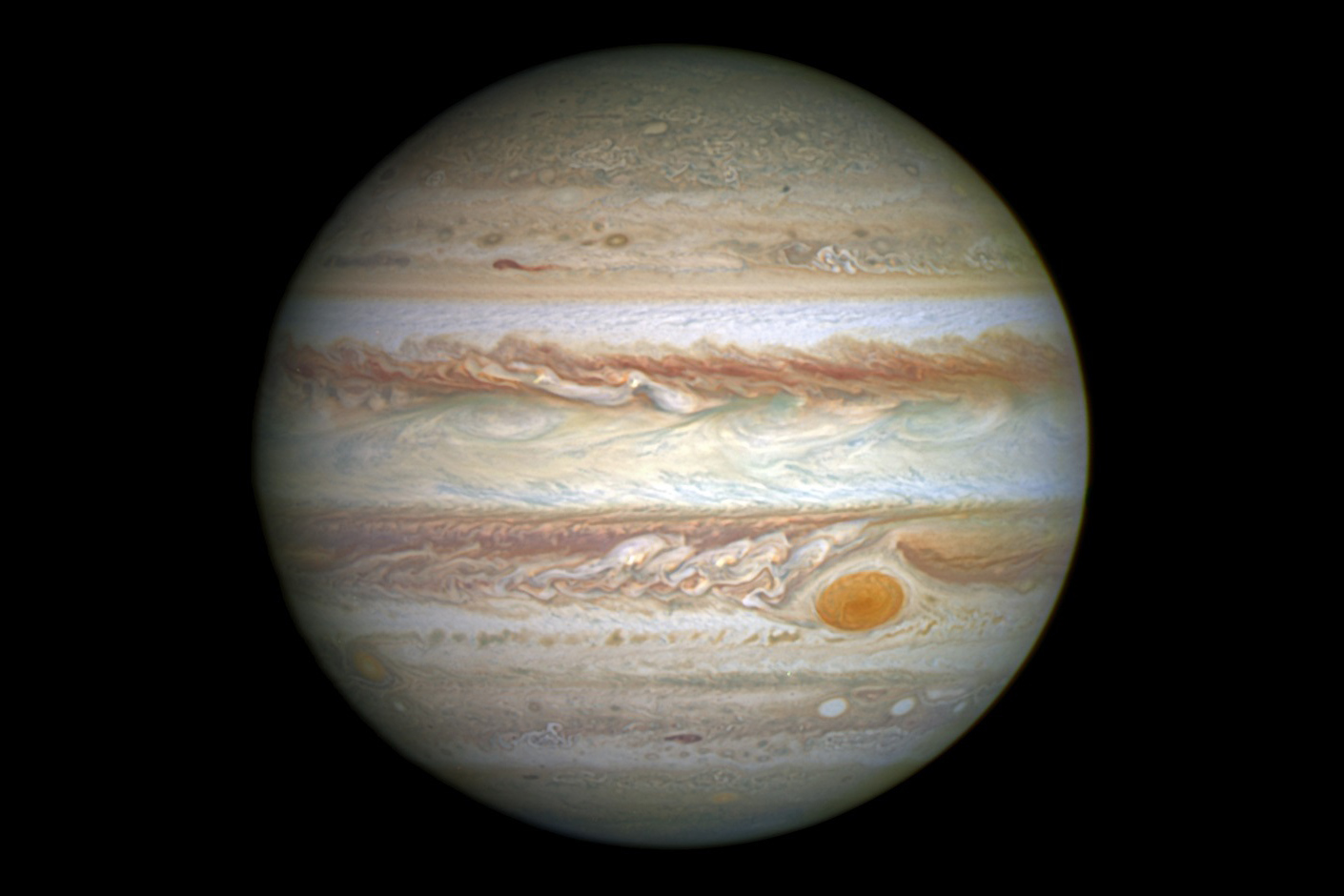

Jupiter — the largest planet in our system, the mysteries of Jupiter has fascinated astronomers and non-astronomers alike for centuries. Poisonous gases completely cover its surface, hiding what lies beneath and violent storms prevent any landings of probes onto or images taken of the giant planet. Jupiter's atmosphere has been determined to be similar to that of the sun containing elements of hydrogen and helium.

Jupiter — the largest planet in our system, the mysteries of Jupiter has fascinated astronomers and non-astronomers alike for centuries. Poisonous gases completely cover its surface, hiding what lies beneath and violent storms prevent any landings of probes onto or images taken of the giant planet. Jupiter's atmosphere has been determined to be similar to that of the sun containing elements of hydrogen and helium.

Saturn

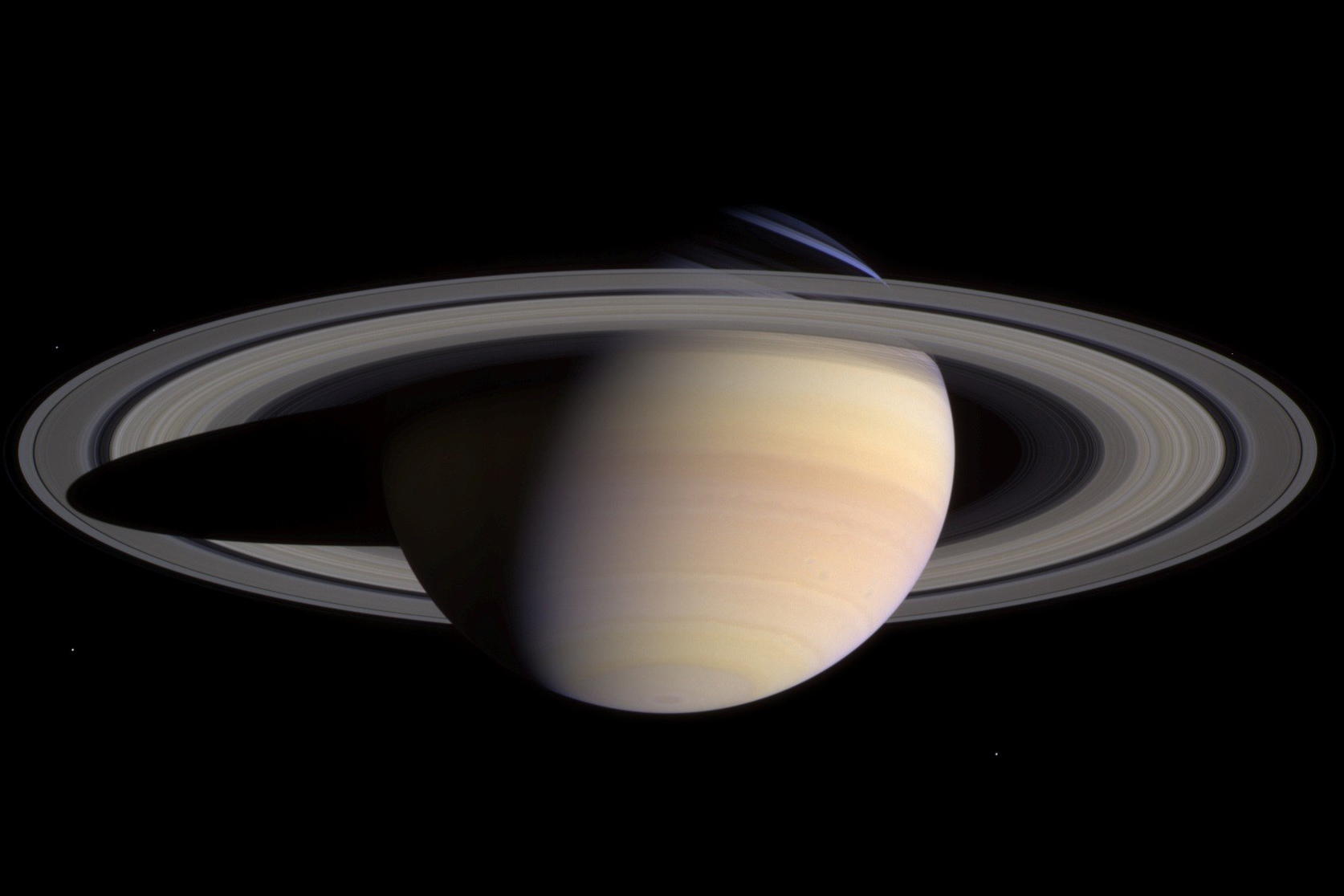

Saturn — first viewed via telescope in 1610 by Galileo Galilei, is the 6th planet in our solar system from the sun. Like Jupiter, its atmosphere is composed primarily of helium and hydrogen and it is the only planet discovered so far that has a lower density than water, approximately 30% lower. It is surrounded by a set of 9 whole rings and 3 broken rings that are comprised mainly of ice, rock, and space "dust".

Saturn — first viewed via telescope in 1610 by Galileo Galilei, is the 6th planet in our solar system from the sun. Like Jupiter, its atmosphere is composed primarily of helium and hydrogen and it is the only planet discovered so far that has a lower density than water, approximately 30% lower. It is surrounded by a set of 9 whole rings and 3 broken rings that are comprised mainly of ice, rock, and space "dust".

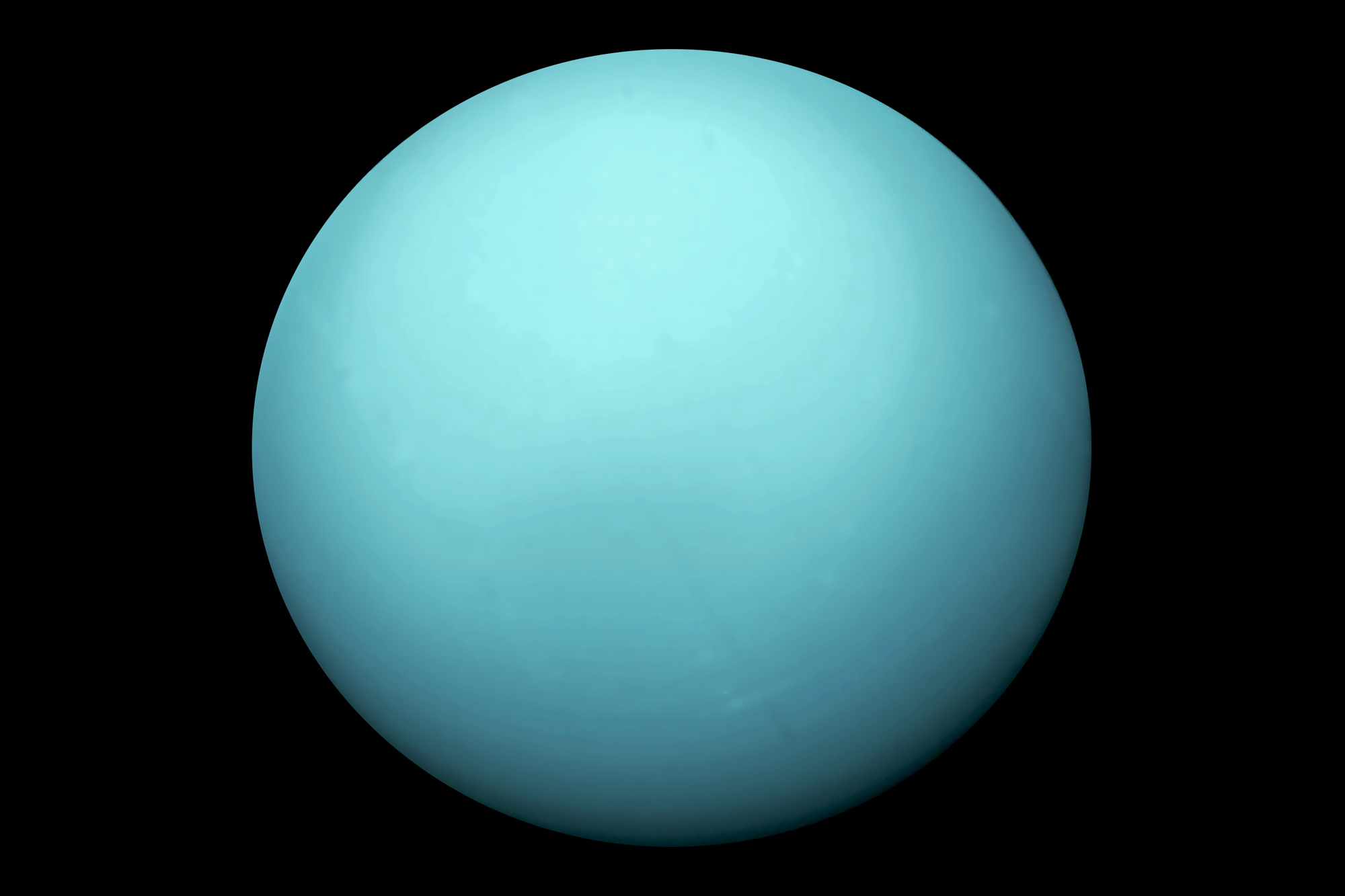

Uranus

Uranus — also known as the "sideways planet" because of its awkward rotation, is the 7th planet in our solar system from the sun. Its North and South poles are located where other planets equators are, given to its strange rotation and its 20 year long seasons. The level of methane gases in its atmosphere account for its bluish color, but the main elements in Uranus' atmosphere is helium and hydrogen.

Uranus — also known as the "sideways planet" because of its awkward rotation, is the 7th planet in our solar system from the sun. Its North and South poles are located where other planets equators are, given to its strange rotation and its 20 year long seasons. The level of methane gases in its atmosphere account for its bluish color, but the main elements in Uranus' atmosphere is helium and hydrogen.

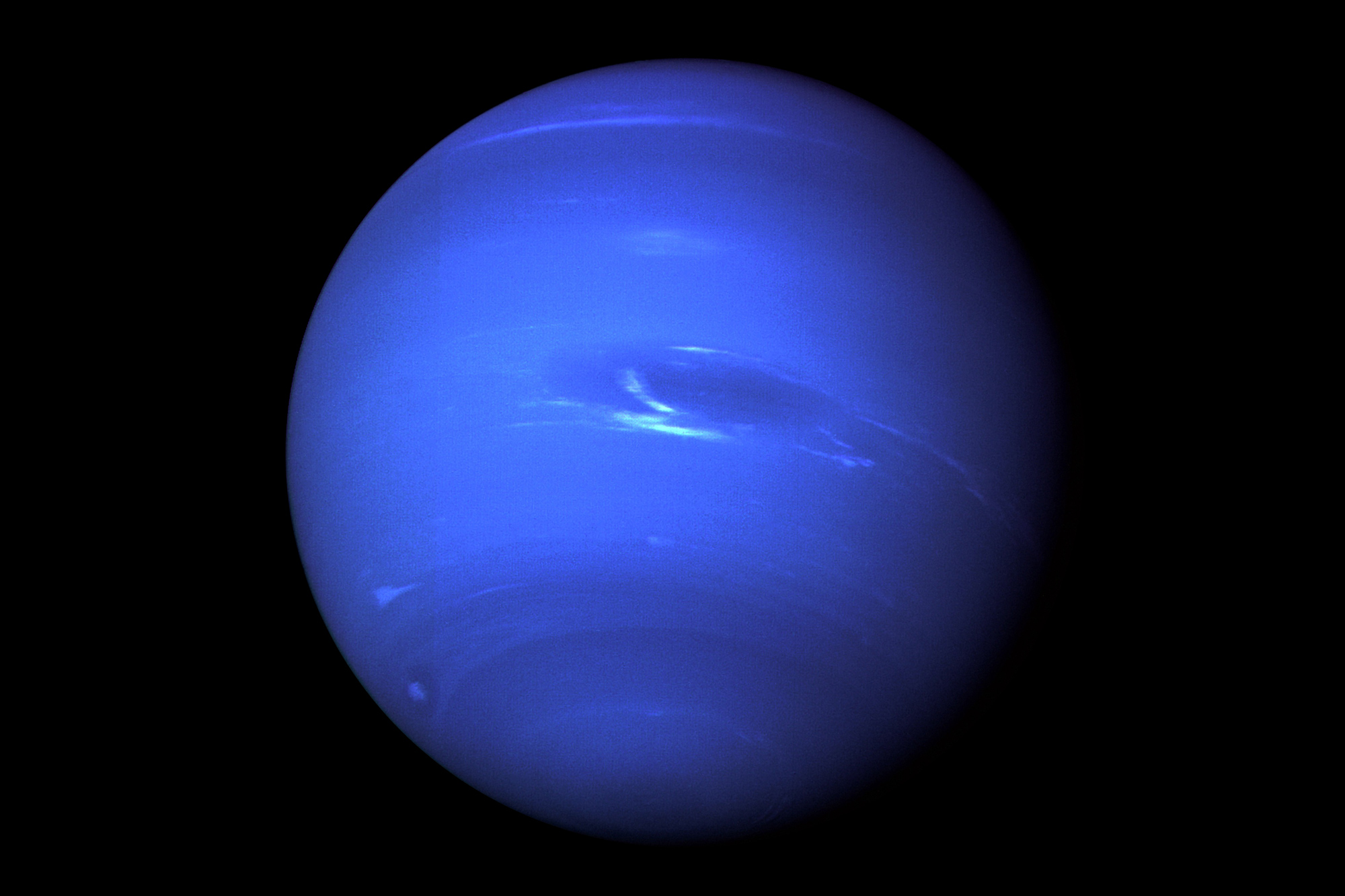

Neptune

Neptune — is known as the windiest planet in our solar system and 8th furthermost known "planet" from our sun. It has a revolution around the sun of 165 Earth years. Like Uranus, Neptune has high traces of methane in its atmosphere, which contributes to its blue color. It is believed there is a second "unknown" element, though, that makes it a much brighter blue than Uranus.

Neptune — is known as the windiest planet in our solar system and 8th furthermost known "planet" from our sun. It has a revolution around the sun of 165 Earth years. Like Uranus, Neptune has high traces of methane in its atmosphere, which contributes to its blue color. It is believed there is a second "unknown" element, though, that makes it a much brighter blue than Uranus.

pluto

Pluto — at one time known as the 9th planet in our solar system, due to the new astronomy rules Pluto is no longer considered a planet but is now a "dwarf" planet. Located beyond Neptune in the Kuiper Belt (ring of bodies past Neptune), Pluto is smaller than our own moon and reaches temperatures of -387°F (-233°C).

Pluto — at one time known as the 9th planet in our solar system, due to the new astronomy rules Pluto is no longer considered a planet but is now a "dwarf" planet. Located beyond Neptune in the Kuiper Belt (ring of bodies past Neptune), Pluto is smaller than our own moon and reaches temperatures of -387°F (-233°C).

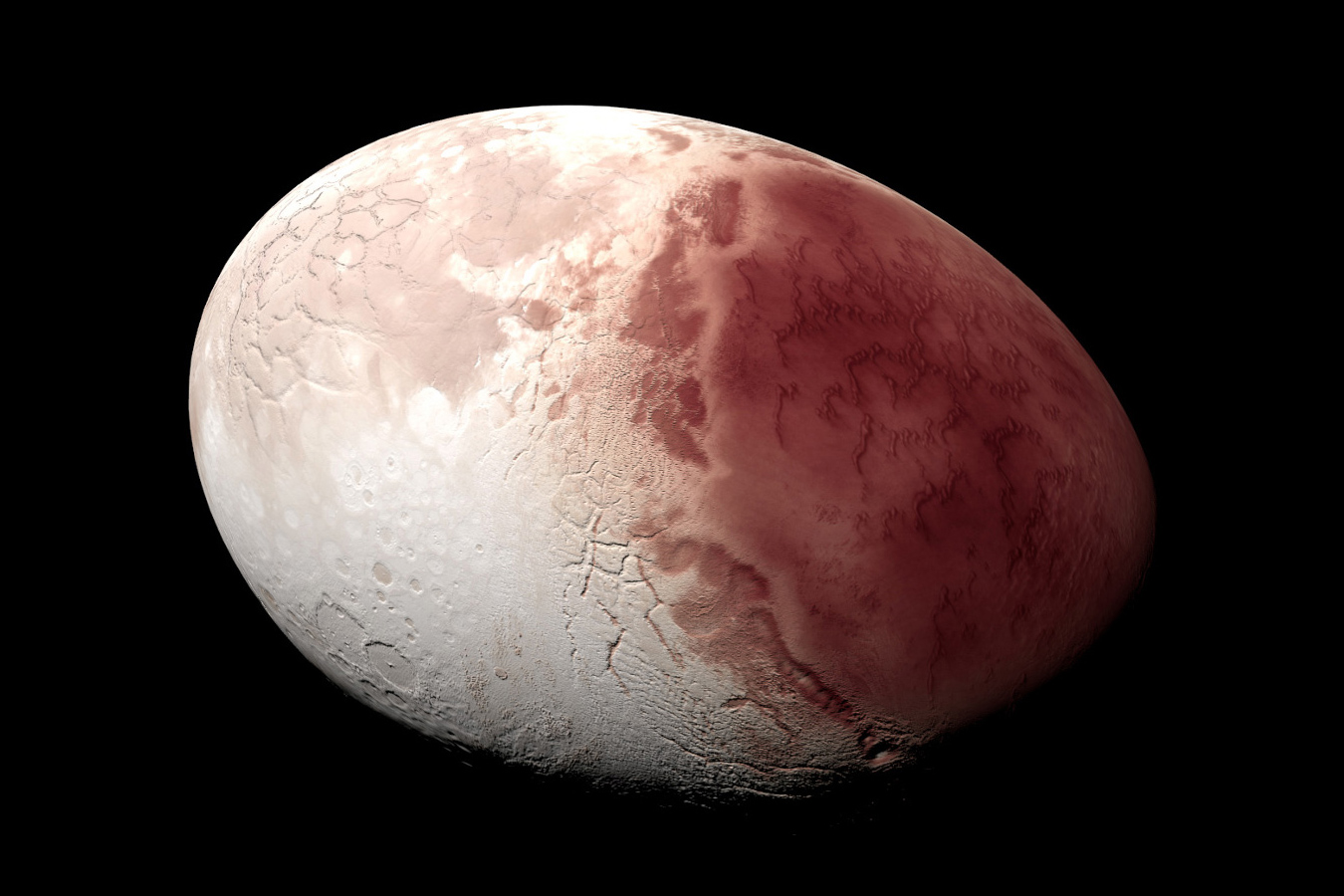

Haumea

Haumea — because of its distance, little is truly known about Haumea other then its odd elongated shape and it is roughly the same size as Pluto. It's orbit path around the sun takes 285 Earth years and it is made up of rock with an icy coating over the surface. This coating causes the dwarf planet to appear bright, similar to the effect of sunlight on snow on Earth.

Makeme

Makemake — is a recently discovered, March of 2005, dwarf planet located in the Kuiper Belt. Slightly smaller than Pluto, Makemake's surface consists of primarily frozen nitrogen, ethane, and methane. Makemake's orbital path around the sun is approximately 310 Earth years and it, along with Eris, is responsible for the new classifications of what constitutes as a planet.

Eris

Eris — the next "dwarf" planet within the Kuiper Belt is Eris and it has the most extreme orbital path that extends well outside of our solar system. It is believed that its surface temperatures varies from -359°F (-217°C) to -405°F (-243°C). Its surface is covered in ice but as it comes closer to the sun and the ice melts, it's surface is closely similar to Pluto's.

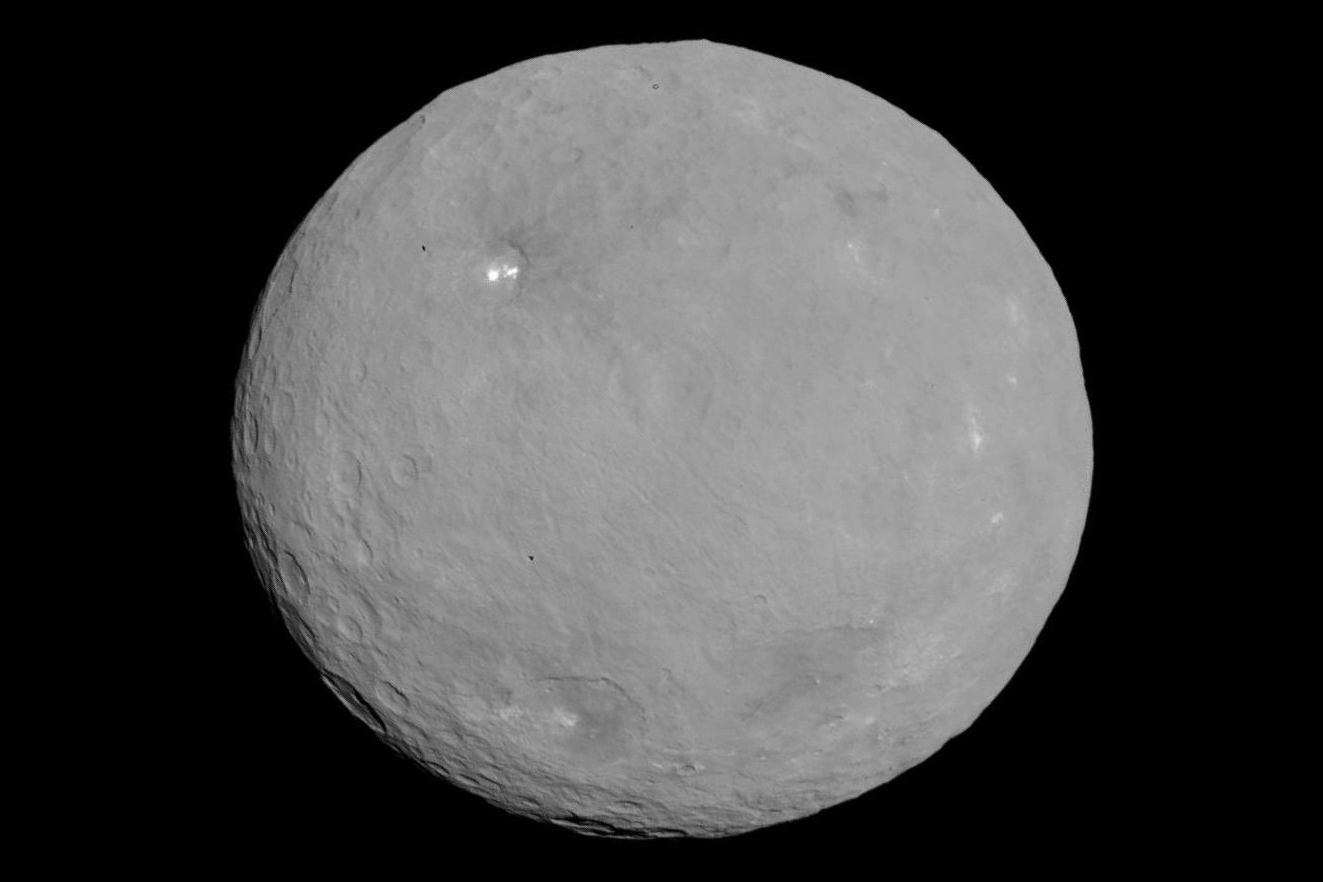

Ceres

Ceres — upon its first discovery in January of 1801, was believed to be a comet then it was determined to be the missing planet between Mars and Jupiter. However, it is nested in an asteroid belt (the largest in our solar system) and so it was reclassified to be an asteroid. It is now considered as a "dwarf" planet, but is still labeled as an asteroid, because in reality, like Pluto, they have no idea how to truly classify this mysterious object.

Planet

Planet X — according to Caltech researchers, there is a strong possibility that there is another planet in the far reaches of our solar system Planet X. Nicknamed "Planet Nine", as it is theorized it is the 9th planet in our system, there is no direct evidence that the planet exists, but there are several mathematical models and computer simulations that point to its existence. It is believed that the planet may be larger than Neptune and have a rotation of 10 - 20 thousand Earth years around the sun.

Planet X — according to Caltech researchers, there is a strong possibility that there is another planet in the far reaches of our solar system Planet X. Nicknamed "Planet Nine", as it is theorized it is the 9th planet in our system, there is no direct evidence that the planet exists, but there are several mathematical models and computer simulations that point to its existence. It is believed that the planet may be larger than Neptune and have a rotation of 10 - 20 thousand Earth years around the sun.